Die Entführung aus dem Serail, K. 384

(The Abduction from the Seraglio)

Singspiel in three acts

German text by Christoph Friedrich Bretzner,

freely adapted by Johann Gottlieb Stephanie, the Younger

Premiere: Vienna, July 16, 1782

Scene: Turkey, the palace of Pasha Selim

Cast, in order of appearance:

Belmonte, a Spanish nobleman, in love with Constanze (tenor)

Osmin, overseer of the pasha's palace (bass)

Pedrillo, Belmonte's servant, in love with Blonde (tenor)

Selim, the pasha (speaking role)

Constanze, Spanish noblewoman, in love with Belmonte (soprano)

Blonde, Constanze's maid, in love with Pedrillo (soprano)

Chorus of Janissaries

Orchestra:

Piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (double on basset horns), 2 bassoons,

2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, percussion, and strings

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

In 1778, the emperor Joseph II established the National Singspiel in Vienna. It was set up as a branch of the National Theater, which he hoped would promote German-language opera, but the company did not do well at first. Not only were its productions weak, but it had to fight a strong taste among the Viennese public for Italian opera and French drama. After three unsuccessful seasons, the company appointed a new director, the actor and playwright Gottlieb Stephanie, the Younger. A friend of the Mozart family, he managed to secure a commission for Wolfgang, who had only recently moved to Vienna from his native Salzburg. It was a valuable opportunity for the young composer to establish his reputation in the capital.

In late July of 1781, Stephanie gave Mozart a play by the Leipzig playwright Christoph Friedrich Bretzner, which Mozart was to set to music and rehearse in less than seven weeks. It was to be presented at festivities for the visit of a Russian Grand Duke, but eventually, the emperor was persuaded that the occasion called for a more dignified entertainment than a singspiel. The premiere was postponed -- for nearly a year, as it turned out -- giving Mozart what was for him a lengthy period of time in which to let his drama evolve. It was a luxury he would never have again.

He began to work more slowly, making alterations and cuts in his music and asking for changes in the libretto. "In an opera the poetry must be altogether the obedient daughter of the music," he wrote. Stephanie himself undertook the task of altering the libretto, making a free adaptation of Bretzner's play. He changed a number of details in the story, turned some sections of poetry into prose dialogue, and transformed some of the spoken scenes into extended musical ensembles. Bretzner was offended at the liberties taken with his play and took out an ad in a Vienna newspaper to object: ". . . a certain person by the name of Mozart in Vienna has had the audacity to misuse my drama Belmonte und Constanze as an opera text. I hereby protest most solemnly. . ." (In his favor, it should be added that he later relented and came to appreciate Mozart's music.)

The premiere took place on July 16, 1782 with a first-class cast that included popular singers of the day. By the second performance, however, a cabal was organized against Mozart's new opera, a routine treatment for outsiders. He described it in a letter to his father: "Can you believe it, but yesterday there was an even stronger cabal against it than on the first evening! The whole first act was accompanied by hissing. But indeed they could not prevent the loud shouts of bravo during the arias." He was then accused of plagiarizing some of the music from Gluck and others -- even though Gluck himself was so impressed that he invited Mozart to dinner after hearing it. Nonetheless, the general public loved the work, and The Abduction from the Seraglio established Mozart's reputation throughout German-speaking lands. It became the first major success of the National Singspiel and one of the greatest successes of Mozart's life.

Turkey and Mozart's Turkish music

The story of The Abduction from the Seraglio reflects eighteenth-century Europe's fascination with the Turks and Islam. On the one hand, the comic but cruel Osmin reflects the old European view of Islam as something quite foreign and barbaric. On the other hand, an eighteenth-century Enlightenment outlook turns the Pasha into a moral exemplar who can hold up a mirror to the faults of European civilization. The Pasha releases his prisoners in the end, in order to show his enemy, Belmonte's father, that justice is more deeply satisfying than cruelty. The Pasha, who only speaks in this drama, thus becomes the pivotal figure in the story. Interestingly, this altruistic twist in the plot was one of Stephanie's alterations. In the original play, the Pasha spares his prisoners because he discovers that Belmonte is really his long lost son.

By the time of The Abduction, Turkish janissary music was very much in vogue. Turkish military bands were imported into Europe and imitated by many local rulers, and their musical style found its way into many European compositions. The music was typically simple and chordal with strong accents, and its characteristic sonority came from a percussion section that included cymbals, triangles, and tambourines, as well as bass and side drums. In the nineteenth century, these instruments found their way into the symphony orchestra as colors in the orchestral palette, but in Mozart's day, they were still used mainly to conjure up images of the Ottoman empire. In The Abduction, Mozart calls for cymbal, triangle and bass drum, as well as piccolo, specifically for the choruses of janissaries. These moments, he told his father, were meant as crowd pleasers: "The janissary chorus is everything that one can desire in a janissary chorus -- short and jolly, and written entirely for the Viennese."

A few arias have been criticized as having dramatic problems. The most notable of these is perhaps Constanze's great, defiant showpiece, "Martern aller artern" ("Torture of all kinds"). Its unusually lengthy introduction (60 measures) is a beautiful concertante piece featuring four solo instruments, but it can be difficult to fill that time with effective staging. It is one of several such moments in the opera that present challenges to stage directors.

But such issues are outweighed by all the music in this opera that was popular with Mozart's Viennese audiences, as well as with audiences today, including a great deal of non-Turkish music. Belmonte's beautiful aria, "O wie ängstlich," was particularly well received and was Mozart's personal favorite. The trio, "Marsch, marsch, marsch," at the end of the first act was another calculated crowd pleaser. Mozart described it to his father: ". . .The major section begins pianissimo-- which has to go very quickly--and the close will make quite a bit of noise. And certainly that is everything the end of an act needs--the more noise, the better; the shorter, the better -- so people do not grow too cold to applaud."

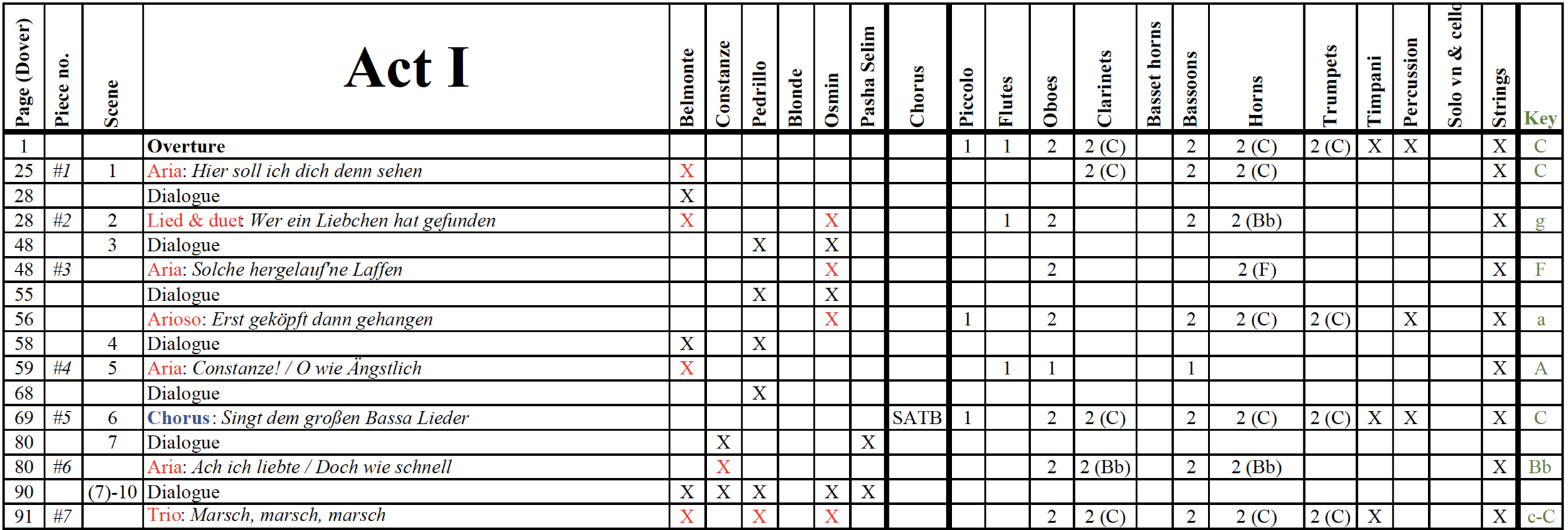

Orchestration Chart

This chart gives an overview of the work, showing which soloists and instruments are in each movement. It has also been useful in planning rehearsals, since one can see at a glance all the music that a particular musician plays. Red X's indicate major solo moments for a singer. An X in parentheses indicates that the use of that instrument is ad libitum.

This is a preview of the beginning of the chart. You can download or view a PDF of the whole chart here.

© Boston Baroque 2020

Boston Baroque Performances

Die Entführung aus dem Serail, K. 384

May 17 & 18, 1996

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Richard Clement - Belmonte

Sally Wolf - Constanze

Jane Giering-De Haan - Blonde

Philip Creech - Pedrillo

Kevin Langan - Osmin

Will Le Bow - Pasha Selim