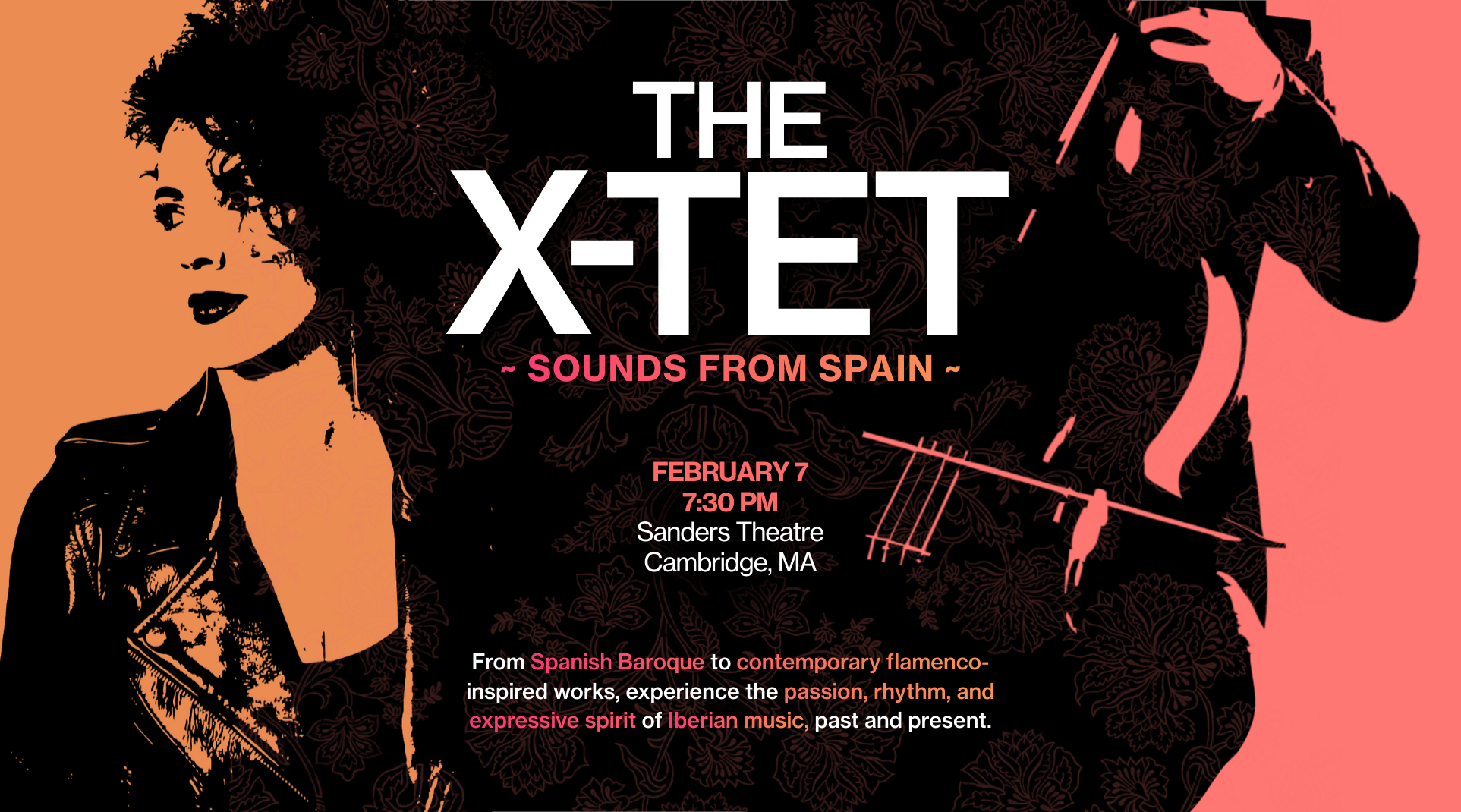

2025-26 Season > The X-tet: Sounds From Spain

Boston Baroque’s February concert explores the vibrant, dance-driven musical traditions of Spain, from the Baroque to contemporary compositions. The program features songs performed by tenor Karim Sulayman, works by Barcelona-born composer Olivia Pérez-Collellmir, and instrumental selections highlighting Spanish Baroque forms with baroque guitar and percussion.

The repertoire journeys through emotional extremes and infectious rhythms, centering on Folias, Tarantellas, and love songs, while showcasing both historical masterpieces and modern interpretations. Highlights include Vivaldi’s La Follia, Boccherini’s “Fandango” Quintet, Durón’s passionate arias, and Pérez-Collellmir’s contemporary “Tangos a Mompou” and “Granada”. Traditional Sephardic folk songs and festive Spanish dances interweave throughout, creating a rich tapestry of Iberian music past and present.

Curated by Christina Day Martinson, Boston Baroque’s Associate Artistic Director, this program celebrates the expressive spirit, rhythmic vitality, and cross-cultural and cross-generational resonance of Spain's musical heritage, brought to life by Boston Baroque’s chamber ensemble.

Estimated Run Time

2 HRS | 20-minute Intermission

Location

Harvard’s Sanders Theatre | 45 Quincy St, Cambridge, MA 02138

ARTISTS

violin

Christina Day Martinson

Learn More >

composer

Olivia Pérez-Collellmir

Learn More >

tenor

Karim Sulayman

Learn More >

LISTEN

The following works were composed by Olivia Pérez-Collellmir and have been newly arranged for period instruments for this performance.

PROGRAM

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

Tarantella Napoletana (Arr. Jeff Louie)

Tarantella del Gargano - Traditional Folk Song (Arr. Jeff Louie)

Rafael Antonio Castellanos (1725-1791)

Oryan Ina Xacarilla

Anonymous

Ay Amor Loco (Oh, Crazy Love!) (Arr. Jeff Louie)

Sebastián Durón (1660-1716)

No. 10 Sosieguen, descansen

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Sonata n.12 in d-minor La Follia (RV 63)

- INTERMISSION -

Anonymous

Avrix, mi Galanica (“Come in my loveley”) - Traditional Sephardic Folk Song

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

No se emenderá jamás, HWV 140 (My heart will never mend for loving you)

Andrea Falconieri (1585-1656)

Folias de Esapaña

Santiago de Murcia (1673-1739)

“Marizápalos”

Sebastián Durón (1660-1716)

Ay, que me abraso de amor en la llama (Oh, I burn with love in the flame)

Anonymous

Adio kerida (Goodbye my love) - Traditional Sephardic Folk Song

La prima vez (The First Time) - Traditional Sephardic Folk Song

Olivia Pérez-Collellmir

Granada

Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805)

Fandango, Quintet in D major 448

Olivia Pérez-Collellmir

Tangos a Mampou (Arr. Olivia Pérez-Collellmir and Chanos Domínguez)

COMPOSERS

Olivia Pérez-Collellmir

Olivia Pérez-Collellmir is a Barcelona-born pianist, composer, and bandleader whose music fuses classical virtuosity with influences from flamenco and jazz. Described by The Arts Fuse as a “Spanish virtuoso” who adds “a flamenco touch to her chamber jazz,” she has performed internationally at venues including the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, El Gran Teatre del Liceu, and SOB’s in New York, and has appeared with artists such as Rosana Arbelo, Sonia Olla, and Ismael Fernández. A Berklee College of Music alumna and current faculty member, Pérez-Collellmir is the recipient of Berklee’s Piano Chair and Piano Achievement Awards and founded the school’s first Contemporary Spanish Music and Flamenco Jazz Ensemble. Her debut album, Olivia (Adhyâropa Records, 2023), features her original compositions and collaborations with Judit Neddermann, John Lockwood, and others, supported by a Berklee Faculty Fellowship Grant.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

George Frideric Handel, one of the towering figures of the Baroque era, was a composer of remarkable versatility whose music reflects the cosmopolitan influences of early 18th‑century Europe. Among his lesser‑known explorations is his engagement with Spanish language and rhythm. He composed works such as the cantata No se emenderá jamás (HWV 140), written in Spanish for soprano, guitar, and basso continuo, demonstrating his ability to adapt foreign idioms naturally into his style. Handel also drew on Spanish dance forms—like the sarabande, which he often incorporated into keyboard and orchestral suites—bringing the distinctive triple‑meter rhythms and expressive character of Spanish music into the Baroque repertoire. These elements reveal a composer attuned to diverse musical traditions, blending elegance, dramatic vitality, and cross‑cultural nuance.

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Antonio Vivaldi, the Venetian Baroque composer renowned for his concertos, also engaged with Spanish musical traditions. He drew on the folia, a dance-based harmonic progression with roots in the Iberian Peninsula, in works such as his La Folia variations for two violins and continuo. Vivaldi incorporated Spanish-influenced dance forms like the sarabande, using slow triple-meter rhythms and expressive syncopations that reflect Iberian stylistic traits. His Lute Concerto in D major (RV 93) further demonstrates a connection to Spanish instruments and repertoire, highlighting the broader European dialogue in which Vivaldi participated. These elements reveal a composer attuned to diverse musical cultures and rhythms beyond his native Italy.

Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805)

Luigi Boccherini, the Italian cellist and composer who spent much of his career in Spain, developed a deeply Iberian-inflected musical voice through his long tenure at the Spanish court. During his time in Madrid under the patronage of Infante Don Luis, Boccherini absorbed local dance idioms like the fandango and seguidilla, weaving their rhythms and guitar textures into his chamber works. His Guitar Quintet in D major, known as the "Fandango," is a prime example of this fusion. In his evocative string quintet Musica notturna delle strade di Madrid (Night Music of the Streets of Madrid), he captures the spirit of nocturnal Madrid, conjuring street sounds, church bells, and folk dancers with vivid programmatic detail. He also composed the zarzuela Clementina, with a Spanish libretto, reflecting his assimilation into Spain’s vocal and theatrical traditions. Boccherini’s music thus stands at the crossroads of classical elegance and Spanish folk vitality, shaped by his deep personal and professional immersion in Spanish culture.

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

Athanasius Kircher, the German Jesuit polymath who spent formative years in Spain, occupies a unique place in the musical and intellectual life of the Iberian Baroque. During his time at the Jesuit college in Madrid in the 1620s, Kircher encountered Spain’s rich sacred, theatrical, and popular musical traditions, experiences that left a lasting imprint on his thinking about sound and music. Immersed in a culture where courtly spectacle, Catholic ritual, and folk practices coexisted, he absorbed Spanish approaches to rhythm, devotion, and sonic symbolism. These influences later surfaced in his monumental treatise Musurgia universalis (1650), where he reflects Spanish sacred polyphony, the dramatic use of music in liturgy, and the power of music to move the passions. Kircher’s engagement with Spanish musical life was less about composition than synthesis: he framed Iberian practices within a universal theory of music that linked science, theology, and art. In this way, his Spanish experience helped shape a vision of music as a global, expressive, and spiritually potent force at the heart of Baroque culture.

Rafael Antonio Castellanos (1725–1791)

Rafael Antonio Castellanos is one of the most important composers of the Spanish colonial world. He developed a musical voice rooted in Iberian sacred traditions while responding vividly to local culture in the Americas. Active in Guatemala City at the Cathedral of Santiago de Guatemala, Castellanos inherited the Spanish cathedral style of polychoral writing, dance-like rhythms, and clear melodic expression shaped by villancicos and devotional songs imported from Spain. He infused these forms with regional color, writing festive sacred works that often incorporated vernacular language, lively rhythms, and accessible textures designed to engage broad congregations. His villancicos for major feast days blend Spanish poetic forms with buoyant, almost theatrical musical gestures, reflecting the role of music as both spiritual instruction and public celebration in colonial Spanish society. Castellanos’s music stands as a bridge between Spanish Baroque practice and New World expression, revealing how Iberian musical traditions were transformed and reanimated in a colonial context.

Sebastián Durón (1660-1716)

Sebastián Durón stands as one of the leading musical voices of late Baroque Spain, shaping a distinctly Spanish operatic and sacred style at the turn of the 18th century. Born in Brihuega and active in Madrid, Durón rose to prominence as maestro de la Real Capilla under King Charles II, where he helped define the sound of the Spanish court. His music draws deeply on Iberian theatrical traditions, particularly the zarzuela, blending Italianate lyricism with Spanish dance rhythms, popular song forms, and vivid dramatic pacing. In stage works such as Salir el amor del mundo and La guerra de los gigantes, Durón employs seguidillas, jácaras, and other vernacular idioms to animate mythological and allegorical narratives with unmistakable local color. His sacred music similarly balances expressive immediacy with courtly refinement, reflecting the close relationship between liturgy and theater in Spanish musical life. Through this fusion of popular and courtly elements, Durón’s works embody the energy, elegance, and theatrical flair of Spain’s late Baroque culture.

Andrea Falconieri (1585-1656)

Andrea Falconieri, the Italian lutenist, guitarist, and composer, developed a musical style deeply shaped by his long association with Spain and the Spanish court. Born in Naples, then under Spanish rule, Falconieri spent significant years in Spain serving as a court musician, where he absorbed Iberian dance forms and performance practices that would become central to his instrumental writing. His music frequently draws on popular Spanish dances such as the folía, ciaccona, and passacaglia, transforming them into refined instrumental works for plucked strings and continuo. Collections like Il primo libro di canzone, sinfonie, fantasie reveal a vivid blend of Italian virtuosity and Spanish rhythmic vitality, marked by bold harmonies, driving ostinati, and an improvisatory spirit closely tied to guitar traditions. Falconieri’s works capture the porous boundary between courtly art music and popular dance, reflecting the cultural exchange fostered by Spanish influence in southern Italy and beyond. His music stands as a compelling example of how Spanish idioms helped shape the emerging Baroque instrumental style across Europe.