Program Notes

by Martin Pearlman

HANDEL's Messiah

December 7 & 8, 2024

One of the special challenges in performing Messiah year after year is to keep the work sounding fresh, as if one had just discovered it. When Boston Baroque gave the first Boston period-instrument performances of the complete oratorio in 1981, the work was still normally heard in this country in the relatively heavy, reverential style of the nineteenth century. It was thus a surprise to many listeners to hear a more detailed, articulate style and quicker tempos based on Baroque dance rhythms and speech patterns. This kind of performance was perhaps less in the spirit of church music—Handel never performed Messiah in a church—and more in the spirit of the theater, or of a “fine Entertainment,” as Handel’s librettist Charles Jennens called it.

Today, such an interpretation is much more common among both period and modern orchestras, and it is no longer surprising. Instead, a listener can focus on the drama of the work and how a particular performance presents it. I personally have found it satisfying to return to the work each year not so much to perform different versions of it or to consciously try to do something “different,” but rather to discover more details and greater depth in the music. For me, that is what makes it perpetually “new.” A work such as Messiah is inexhaustible.

“SPEAKING” AND “SINGING” MUSIC

The chorus has the greatest role of any actor in Messiah. Its music constantly shifts between a kind of “speaking” music, which declaims speech patterns in the text, and a more lyrical “singing” music. Much as dance rhythms can influence the tempo and character of a piece, the speech patterns of the text can often suggest a natural tempo. But “speaking” music is not only rhythmic; it also has very flexible, detailed dynamics, as in actual speech, where the sound of even a single syllable may sometimes die away. A more powerful type of spoken declamation often comes at climactic moments, such as at the words “Wonderful, counselor” in the chorus

“For unto us a child is born.” The playing of the orchestra too reflects the rhythmic quality and detailed dynamics of the speech patterns in the text, an effect more easily achieved on Baroque than on modern instruments.

THE LIBRETTO AND THE DRAMA

In creating his libretto, Charles Jennens interspersed texts from both the Old Testament prophets and the New Testament, frequently using metaphor—rarely narrative—to depict in a general way the story of the Messiah. Although the oratorio is primarily contemplative, with no speaking characters and hardly any action, it does fall into several dramatic scenes, which demand a degree of continuity between movements in performance. The first scene, running from the overture through the chorus “For unto us a child is born,” prefigures the arrival of the Messiah. The second opens with an instrumental interlude depicting the shepherds’ pipes (Pifa) and the angel announcing the birth of Jesus; it is the only true narrative moment in the oratorio and ends with the angels slowly disappearing as the music fades away. Part I concludes with rejoicing.

Part II falls into two large scenes, the first reflecting on the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus, and the second depicting the spread of the Gospel. Part III is a section of contemplation and thanksgiving, based on the Anglican burial service.

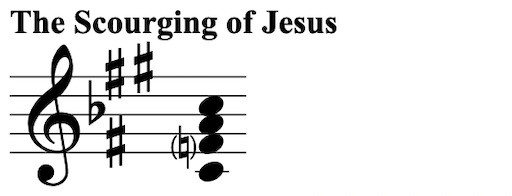

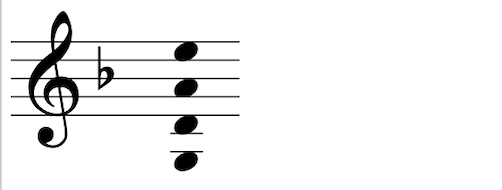

In places, these scenes are unified by recurring figuration in the music: the sharp, dotted rhythms representing the scourging of Jesus in Part II first appear in the middle section of the aria “He was despised”, then again in the following chorus (“Surely, he hath borne our griefs”), and yet again in the recitative (“All they that see him laugh him to scorn”). Sometimes scenes are unified by pieces in related tempos or in similar affects. An example of the latter occurs at the end of Part II, where a string of violent images (“Why do the nations so furiously rage together”, “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron”) is crowned with the chorus “Hallelujah.” In this context, “Hallelujah” becomes not only a shout of joy but also something of a war cry.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

When Charles Jennens presented Handel with his text for Messiah in 1741, Handel’s fortunes were so low that he was considering leaving England. Several years earlier, his opera company had collapsed, and he had suffered a stroke. In the years following his recovery, he had had great success with two English oratorios (Saul and L’Allegro), but his two Italian operas had been complete failures. With the fashion for Italian opera apparently over, Jennens hoped to persuade Handel to return to writing English oratorios.

In the summer of 1741 came a fortuitous invitation to give a series of concerts in Dublin. With these concerts in mind, Handel set to work on the music for Messiah on August 22, completing the enormous work on September 14, a mere three weeks later. Jennens, never one to be overly modest, expressed disappointment that Handel had not spent a year setting his libretto. “[Handel] has made a fine Entertainment of it, tho’ not near so good as he might & ought to have done. I have with great difficulty made him correct some of the grossest faults in the composition, but he retain’d his Overture obstinately, in which there are some passages far unworthy of Handel, but much more unworthy of the Messiah.”

Messiah was premiered on April 13, 1742 in Dublin for the benefit of charity and drew so many people that ladies were requested not to wear hoops, in order to accommodate a larger audience. The series of concerts was a triumph. According to Faulkner’s Journal, “The best judges allowed it to be the most finished piece of Musick. Words are wanting to express the exquisite Delight it afforded to the admiring crowded Audience.”

But Handel was wary about presenting his new oratorio in London. Several years earlier, Israel in Egypt had failed, partly due to a controversy over using a biblical text in the theater. When he did finally introduce Messiah there in 1743, it was not well received, partly indeed because of its biblical text, but also partly because there were too many choruses and no characters playing out a story. The work did not become widely accepted until Handel began presenting it in his annual charity performances for the Foundling Hospital in 1750. Between that time and Handel’s death in 1759, Messiah attained the exalted stature it has held to the present day, a musical tradition unparalleled in the English-speaking world.

PERFORMING VERSION

In Messiah, as in many of his other works, Handel made numerous changes for later performances. Many of these changes were made simply to accommodate a new singer, such as changing an aria from one voice range to another, and do not necessarily reflect his final preference for how a movement ought to go. Other changes, however, appear to be attempts to improve the work and must be taken into account in a modern performance. There is no definitive version. A modern performer must look at the various versions presented in the different manuscripts (sometimes there is more than one version in the same manuscript), try to understand the reasons for the changes, and make decisions about the best version to use.

Handel’s autograph score survives, and, while it contains the original version of the work, he seems to have changed his mind about certain pieces even before the first performance. At least as important as the autograph is a score which Handel apparently used in Dublin and in certain later performances. It is in the hand of Handel’s copyist, but Handel himself has made many changes and marginal notes, including writing in names of singers. A third important version is a manuscript, again by a copyist, bequeathed by Handel in his will to the Foundling Hospital, for which he had given benefit concerts. This Foundling Hospital score appears never to have been used, but with it there is a valuable set of orchestral and vocal parts which formed the basis for many of his later performances. There are other sources, but these three—the autograph, Dublin and Foundling Hospital—have the greatest authority from Handel’s own performances. Our performance this evening is based on the Dublin score, the one used for the first performances, and it incorporates Handel’s later corrections in that score.

ABOUT STANDING DURING “HALLELUJAH”

Over the years, many people have asked us about the tradition of the audience standing up for the “Hallelujah” chorus. Some people, citing concerts at which they were asked not to stand, have thanked us for allowing them to follow tradition. Others have expressed dismay at seeing the audience get to its feet, blocking their view of the stage, and felt pressured to join in. In the middle have been some who are unsure whether to stand or to remain seated.

The custom of standing comes from after Handel’s time, when Messiah—and particularly “Hallelujah”—was treated more as a cultural icon than as a piece of music. There is certainly no historical reason to stand, but then we do not require our audiences to put on historical performances. The performances are for your pleasure and we would encourage you to sit or to stand as you wish, and enjoy the glorious music that closes Part II of Messiah.

Program Notes

by Martin Pearlman

Mozart’s Requiem and Symphony No. 40

October 22, 2017

MOZART, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550

This well loved symphony dates from the summer of 1788. It was a time when Mozart's public career and personal finances were faltering, and he had only recently suffered the death of a baby daughter. Nonetheless, it was an unusually productive year for his composing, with thirty new entries in his catalogue of works. Don Giovanni, written the previous year, was produced in Vienna in May of 1788, and in June he began work on his final trilogy of symphonies, of which this is the second, completing all three in less than two months.

This G minor symphony was already popular and highly esteemed by the early 19th century, due not only to its brilliant writing but also, no doubt, to its "romantic" qualities, among them its unusually quiet and agitated opening and the dark color of its minor key. (It was one of only two Mozart symphonies written in minor.)

Mozart later revised the wind parts of this symphony to add clarinets. Our performance today is of the more lightly scored original version.

MOZART, Exsultate, jubilate, K. 165

Mozart was 16 years old when he composed his best known solo motet, Exsultate, jubilate. The three-movement work, a favorite show piece for sopranos today, was originally written for a castrato. Boston Baroque's 2010 recording of it for Telarc thus featured a male soprano.

The famous soprano castrato Venanzio Rauzzini, for whom it was composed, had been a principal at the opera in Vienna for several years and served at the electoral court in Bavaria. Mozart had come to know him in Milan, when he was hired to sing the premiere of the young composer's opera Lucio Silla. Mozart then went on to write Exsultate, jubilate for him a month later, in January of 1773.

In the following year, Rauzzini moved permanently to England and established himself in 1777 at Bath, where he lived for the remainder of his life. There he directed a concert series, sang, composed a great deal of music, and became the esteemed teacher of many fine singers, among them Nancy Storace and Michael Kelly, both of whom later worked with Mozart in Vienna. One contemporary journal called him "the father of a new style in English singing." In 1794, he was visited at his home by Haydn, who, seeing Rauzzini's bereavement at the loss of his beloved dog Turk, composed a canon setting the words on Turk's tombstone. A portrait of Rauzzini with his dog hangs in the Holburne Museum of Art in Bath.

MOZART, Requiem in D minor, K. 626

In mid-1791, when he was working on The Magic Flute, Mozart was visited by a stranger who commissioned him to write a requiem. He offered Mozart a significant fee—half of it in advance—on the condition that it be anonymous. The secret patron behind the commission was Count Franz von Walsegg, who intended to pass off the work as his own composition in memory of his recently departed young wife.

Toward the end of that year, after completing The Magic Flute and fulfilling a late commission for another opera,

La Clemenza di Tito, Mozart was able to become fully engaged in writing his requiem. By that time, however, he was seriously ill and needed to dictate some of his composition to an assistant. His friend Benedikt Schack—the tenor who sang Tamino in The Magic Flute—relates that, on the afternoon before Mozart died, the composer had the unfinished manuscript of the Requiem brought to him in bed and sang through the vocal parts with several friends. Schack tells us that Mozart himself sang the alto part but got only as far as the Lacrimosa, at which point he broke into tears and put the score aside. He died during that night of December 5, age 36.

COMPLETING THE REQUIEM

In the manuscript that Mozart left at his death, only the opening section, the Introit, was more or less complete. Beyond that, nine more sections were sketched; that is, the vocal solo and choral parts plus the orchestral bass line were filled in for the Kyrie through the Hostias, although the famously beautiful Lacrimosa broke off completely after only 8 bars. In these movements, there are just occasional hints at figuration for the orchestra. Missing entirely were the final movements: Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus Dei, Lux aeterna, and Cum Sanctis tuis.

In order to receive the sizable fee for the commission, Mozart's widow Constanze needed to have the score secretly completed and presented as her husband's work. She first turned to Joseph Eybler, a composer and former student who had been well respected by Mozart. Eybler orchestrated some parts of the work but then declined to complete the task for reasons that we can only speculate about. Did he perhaps find it too daunting to work in Mozart's shadow, especially with some movements not even begun? After a couple of other musicians declined the task, Franz Xaver Süssmayr agreed to take it on. Süssmayr had been a family friend and a student of Mozart, but he was considerably less skilled as a composer than Eybler.

In order to complete the Requiem, he had to finish the orchestration, extend the fragmentary Lacrimosa into a complete movement, and compose the missing Sanctus and Benedictus from scratch. For the closing Agnus Dei and Communion, he decided to adapt Mozart's own music from the beginning of the work, setting it with the appropriate text for the end of a requiem.

Although Süssmayr's work has long been considered the standard completion of the work and is thus the one most frequently performed, it has been controversial for at least 200 years. His effort has frequently been criticized as being weak and un-Mozartean in many passages, for containing basic errors of musical grammar, and for being too thickly orchestrated for a Mozart work, with its extensive instrumental doubling of voice parts.

Nonetheless, it is the one version that comes not only from the 18th century but from Mozart's inner circle. It may, for all we know, incorporate some verbal instructions from the composer himself or original sketches that are now lost to us. Indeed, the sections that Süssmayr claimed to be his own (Sanctus and Benedictus) have often been considered too good to be his, considering the quality of his own original music, and are thus suspected of incorporating some of Mozart's instructions. Constanze recalled giving him a "few scraps of music," along with the unfinished manuscript, and her sister, Sophie Haibel, claimed that, on the night before he died, Mozart had given Süssmayr directions as to how he wanted the work completed. But these were memories from several decades later, and it is impossible to know how accurate they were or even whether there may have been a wish to make the work more fully Mozart's. Nevertheless, they are additional reasons not to dismiss Süssmayr's work entirely, despite its problems.

THE LEVIN VERSION

In 1995, Boston Baroque recorded for Telarc the period-instrument premiere of Robert Levin's soon-to-be-published version of the Requiem. Several other new versions had come out in the previous decades, but what was particularly attractive about this one was not only its scholarly grounding but also its respect for the history of the work and its effort to repair and improve the familiar Süssmayr version, rather than to replace it.

The repairs range from many small details to significant changes in the orchestration, as well as bold left turns in the harmony that have surprised those who know the Requiem in the traditional version. The orchestration, which is new in many places, is more transparent than Süssmayr's, errors in voice leading have been corrected, and awkward harmonic progressions have been made more Mozartean. The Hosanna fugue at the end of the Sanctus has been extended beyond Süssmayr's rather timid effort, giving it proportions more typical of Mozart.

Perhaps the most striking new material in this version is the Amen fugue at the end of the Lacrimosa. With Mozart's manuscript breaking off before the end of that movement, Süssmayr brings it to a simple close with the word "Amen." However, in 1963, a sketch in Mozart's hand was discovered that had counterpoint for the opening bars of a fugue, material that appeared to have been meant for an Amen at the end of the movement. Levin has worked the fragment into a completed fugue which, unlike some earlier efforts, remains in a single key throughout, as did Mozart's fugues for similar endings.

Perhaps Mozart himself may have done something along these lines, or he may instead have mixed the material with more modern, homophonic music, as he sometimes did in other works—or he might simply have discarded the sketch and ended the Lacrimosa without a fugue. Did Süssmayr mistakenly overlook the sketch, or, as Christoph Wolff has wondered, did he lack the confidence to write a full fugue in a Mozart work? Did Mozart himself decide to discard it? We will probably never know, but Levin has given us a possible way of listening to this movement as an extended piece. At the same time, we feel a tragic sense of loss as this fragment of music passes from the eighth to the ninth bar of the Lacrimosa dies illa ("On that day of tears"), where Mozart's manuscript abruptly breaks off and that of the completion takes over.

Program Notes

by Martin Pearlman

Handel’s Agrippina

April 24 & 25, 2015

“The audience was so enchanted with [Agrippina], that. . . the theatre at almost every pause, resounded with shouts and acclamations of viva il caro Sassone! [long live the dear Saxon] and other expressions of approbation too extravagant to be mentioned. They were thunderstruck with the grandeur and sublimity of his style: for never had they known till then all the powers of harmony and modulation so closely arrayed, and so forcibly combined.”

This account is by Mainwaring, Handel’s first biographer, who was born well after the event. Whether or not the audience experienced the “harmony and modulation” in exactly this way, there is no doubt about the resounding success of Handel’s second opera. It ran for an extraordinary 27 performances and established the 24-year-old composer’s reputation throughout Europe. It was the first huge triumph of his career.

Agrippina was written toward the end of Handel’s formative years in Italy, and the first performances took place in Venice at the theater of San Giovanni Gristostomo during the winter carnival season of 1709–1710. The cast included some of the most famous names in opera, including Margherita Duras- Tanti, for whom Handel created the title role and who later went on to sing many of Handel’s operas in England. Poppea was sung by the soprano Diamante Maria Scarabelli, whose virtuosic technique inspired Handel to add a flashy aria to the opera during its initial run. Interestingly, the role of the hero Otho was written for a woman (Francesca Vanini-Boschi), and we therefore have a woman singing it in our production. The high role of Nero, however, was sung by a man, the castrato Valeriano Pellegrini; for that role, we have cast a man singing countertenor.

The music of Agrippina has the wonderfully fresh and inventive spirit of Handel’s youth. But it is not entirely original: despite the fact that Handel was still a young man, he recycled many of his own earlier works—mostly works which had previously only been heard in private salons—and, in a few instances, he adapted works of other composers. These “borrowed” works became the basis of his overture and all but five of the arias in this opera, but they were extensively rewritten for Agrippina and brilliantly reveal the characters in each role. As with Messiah, Handel is said to have composed the entire opera in a mere three weeks, a feat that is astonishing even with the borrowed music.

The libretto is by Cardinal Vincenzo Grimani (whose family owned the theater), and it was written expressly for Handel. That was unusual, since, for most of his other operas, Handel turned to libretti in the public domain which had already been set to music by other composers. The characters in this opera, with the exception of Lesbo, are all historical, although Grimani takes liberties with his chronology. Their story derives from the accounts by Tacitus and Suetonius, but here they are treated with a lighter—and sometimes more comical—touch than the characters in those ancient sources, or indeed than the characters in most of Handel’s later operas. Agrippina, the mother of Nero and wife of Claudius, schemes to place her son on the throne while navigating the tangled relationships of Nero, Poppea and Otho. The story has its sequel in the much earlier Monteverdi opera The Coronation of Poppea, which follows the vicissitudes of these last three characters.

Handel’s success with Agrippina changed the course of his life. Among the dignitaries in the audience were Baron Kielmansegge of Hanover and Prince Ernst, the brother of the Elector of Hanover, both of whom went repeatedly to hear the new opera. Handel was soon offered a position at the court in Hanover and left Italy for Germany. As it happened, Germany would be only a brief stop on his path to London, where the greater part of his career would unfold.

Magnificat in D Major, Wq 215

Chorus: S-A-T-B

Soloists: S-A-T-B

Orchestra: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings, continuo

***

Magnificat

Quia respexit (soprano)

Quia fecit mihi magna (tenor)

Et misericordia eius

Fecit potentiam (bass)

Deposuit potentes (alto, tenor)

Suscepit Israel (alto)

Gloria patri

Sicut erat in principio

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the eldest son of Johann Sebastian, wrote his brilliant Magnificat in 1749. It was his first large-scale work, but the reason that he wrote it is a matter of some speculation. At the time, he was employed in Prussia at the court of Frederick the Great, where his principal occupation was as a composer and keyboard player. Whether or not this work was written as an application for another job, as some writers have suggested, it was in all probability not performed until after he had taken a position in Hamburg nearly twenty years later. As music director for the five principal churches in Hamburg, Bach would doubtless have found it useful to resurrect an earlier work such as this to supplement his newer output of religious music. But in resurrecting it, he did not merely dust off the old score, but he recycled parts of this music for other uses in his St. Matthew Passion, his Easter Music cantata, and other works. Late in his life, he appears to have made revisions to this early work and give it a grander sound with the addition of horns, trumpets and timpani.

In much of the son's score, one can feel the influence of the father, who was still alive when this work was first written. Many of the melodic lines and harmonies may be reminiscent of Johann Sebastian, but stylistically Philipp Emanuel's Magnificat is more "modern" than that of his father. Movements in quasi-sonata form look forward to Haydn and Mozart, and some of the harmony even anticipates the nineteenth century. Unlike Johann Sebastian's music, this is for the most part not a contrapuntal work with independent lines. Rather much of the music is homophonic, featuring melodic lines with accompaniments. Even the exhilarating violin parts in the opening movement form a background to simple harmonic writing in the chorus. Only the final movement is in a truly older contrapuntal style. Here C. P. E. Bach creates a double fugue, beginning with a single subject, introducing a second one for the "Amen," and then superimposing the two. Commentators have remarked on the similarity between the first subject and that of the Kyrie in Mozart's Requiem, which was written more than 40 years later. Philipp Emanuel's fugue, however, is extended in length almost to the breaking point, beyond what we find in the fugues of his father or of Mozart. It is a huge capstone to this brilliant early work.

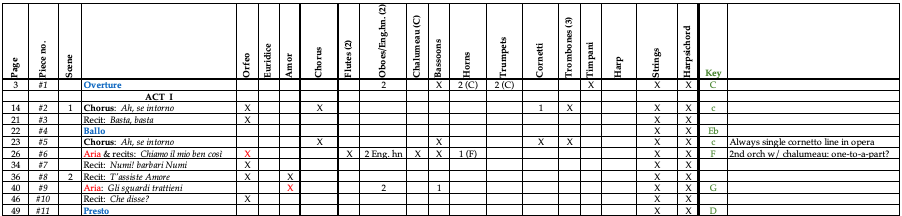

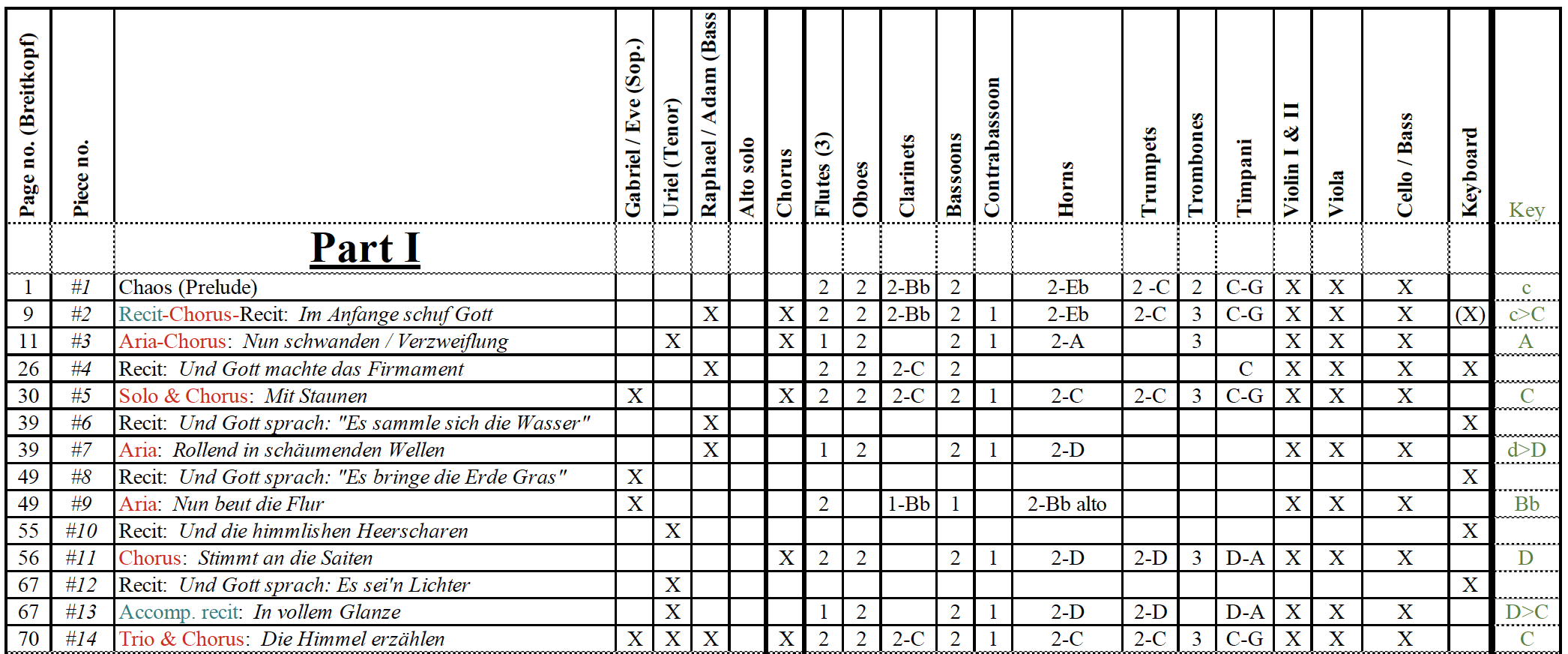

Orchestration Chart

This chart gives an overview of the work, showing which soloists and instruments are in each movement. It has also been useful in planning rehearsals, since one can see at a glance all the music that a particular musician plays. Red X's indicate major solo moments for a singer. An X in parentheses indicates that the use of that instrument is ad libitum.

This is a preview of the beginning of the chart. You can download or view a PDF of the whole chart here.

© Boston Baroque 2020

Boston Baroque Performances

Magnificat

May 7, 1993

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Dominique Labelle, soprano

Mary Ann Hart, mezzo-soprano

Bruce Fowler, tenor

David Arnold, baritone

Six Sinfonias, W. 182

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

By the early 1770's, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was established as Telemann's successor in Hamburg, where he directed music in various churches. Having served nearly thirty years at the court of Frederick the Great, he was already at least as famous and influential as a composer and keyboard player as his father had been in his time.

One of C. P. E. Bach's great admirers was the music enthusiast and Austrian ambassador to Prussia, Baron Gottfried van Swieten. It was he who would later introduce Mozart and Haydn to many of the works of J. S. Bach and Handel and who would write the librettos to Haydn's oratorios The Creation and The Seasons. On a visit to Hamburg to see C. P. E. Bach, van Swieten commissioned him to write a set of symphonies in which, according their contemporary, Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Bach would "give himself free rein, without regard to the difficulties of execution which were bound to arise." The result was a set of six symphonies for strings and continuo completed in 1773. Reichardt wrote of their "original and bold flow of ideas. Hardly has ever a more noble, daring, or humorous musical work issued from the pen of a genius."

These sinfonias have all the qualities that are so characteristic of C. P. E. Bach's musical personality: virtuosic string writing, quirky changes of mood and harmony, and slow movements that take us into the world of the Empfindsamer Stil, the "sensitive" or intimate and introspective style with its arresting chromatic harmonies and highly expressive, melancholy sighing figures. There are dramatic moments that remind us of the Sturm und Drang symphonies that Haydn was writing at the same time. There are also lighter movements, to be sure, but even here there are sometimes surprising harmonic twists under a simple surface.

Reichardt wrote of these sinfonias, "It would be a great loss for art if these masterpieces were to remain hidden away in private hands." Yet they were indeed lost for a time and, on being rediscovered, they were at first mistakenly published as string quartets. The error has been rectified and they have been republished in good editions, but they are still too infrequently heard in concerts today.

Boston Baroque Performances

Sinfonia in B-flat Major, W. 182, No. 2

November 26, 1990

University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH

Martin Pearlman, conductor

November 16, 1990

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Sinfonia in C Major, W. 182, No. 3

November 11, 1988

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Six Symphonies, Op. 3

for 2 oboes, 2 horns, strings and continuo

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782), the youngest son of Johann Sebastian, studied first with his father and, after his father's death, with his brother Carl Philipp Emanuel. He completed his studies in Italy with the renowned musician and scholar Padre Martini, who was later visited by the young Mozart. In Italy, Johann Christian developed a reputation for his liturgical music and operas, and he became a skilled composer of the Italian opera overture, one of the forms that developed into the Classical symphony. In 1762 he moved to London, where he became the queen's music master, a popular composer of operas and instrumental works, and one of the presenters, along with Carl Abel, of an important public concert series. He is often referred to as "the London Bach."

The six symphonies of his Opus 3 were first performed in his concert series in 1765. One member of the audience for some of these works may well have been the nine-year-old Mozart. In 1764-65, Mozart was on tour with his father in England, where he came to know J. C. Bach personally and fell under the influence of his music. Mozart's early symphony, K. 19, written while in London, is modeled on the first of Bach's Opus 3 symphonies. Also while in London, Mozart wrote his first piano concerto, which is actually an arrangement of sonata movements by Bach.

These symphonies of J. C. Bach are in an early Classical style from a time when the symphony was evolving. In their charming themes, the way they develop ideas, and even in their orchestration, one can hear Bach's influence on the young Mozart. But they are more than "lesser Mozart," as some writers have described them. They are lively, attractive works well worth hearing in their own right.

Boston Baroque Performances

Sinfonia in D Major, Op. 3, No. 1

March 13, 1982

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

April 8, 1977

Paine Hall, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Concertos for Harpsichord or Pianoforte, Op. 7

for harpsichord or pianoforte with two violins and cello

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The career of Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian, followed in a general way the same route as that of Handel: Germany to Italy to England. Arriving in England in 1762, three years after Handel's death, J. C. Bach established himself as a popular composer of operas and instrumental works in an early Classical style. It was early in his London years that he was visited by the eight year old Mozart, who was greatly influenced by his music. Mozart's earliest piano concertos were arrangements of Bach's keyboard sonatas, and he esteemed "the London Bach" throughout his life.

Bach's concertos that make up his Opus 7 were published in 1770 under the title Six Concertos for the Harpsichord or Piano Forte with Accompaniments for Two Violins & a Violoncello. In that transitional time between the harpsichord and the piano, it was not uncommon to advertise works as being for either instrument. On the one hand, it could increase sales to people who did not yet have the new pianos, but it also reflected the fact that the piano had not yet developed an idiomatic style distinct from that of the harpsichord.

Bach himself is reported to have performed concerts on the piano as early as 1768, but he is also known to have performed on the harpsichord into the early 1770's. Three of these six concertos have dynamic markings that would suggest performance on a piano: forte markings below just a few notes to emphasize them, as well as progressively loud dynamic markings to indicate a crescendo. For at least those three concertos, the piano would seem to be the preferred instrument, but works from this set have been performed successfully on both harpsichord and piano.

As the publisher's title suggests, these are essentially chamber pieces with only three string instruments accompanying the keyboard soloist. That said, there might also have been performances using a larger ensemble. Horn parts for five of these concertos (all but No. 4), as well as oboe parts for No. 3, were discovered in the late twentieth century, and they appear to be authentic. While the chamber music nature of these works would have made them appealing to amateurs playing at home, a more orchestral version may have been useful for the famous series of concerts that Bach produced in London together with the gambist and composer Carl Friedrich Abel.

Cadenzas by Martin Pearlman

Boston Baroque Performances

Concerto in E-flat Major, op. 7, no. 5

November 14, 1989

Gardner Museum, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

November 10, 1989

Williams College, Williamstown, MA

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

January 27, 1987

Northwest Bach Festival, Spokane, WA

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

October 10, 1980

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, fortepiano soloist

July 23, 1980

Prescott Park, Portsmouth, NH

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

April 2, 1976

University Lutheran Church, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

February 29, 1976

Rockport Opera House, Rockport, ME

Martin Pearlman, harpsichord soloist

Liebster Gott, wann werd ich sterben?, BWV 8

Cantata for the sixteenth Sunday after Trinity

First performance: Leipzig, September 24, 1724

Soloists: Soprano, alto, tenor, bass

Chorus (S-A-T-B)

Orchestra: Flute, 2 oboes d'amore, strings, continuo

(horn colla parte with chorus sopranos)

***

Chorus

Aria (tenor)

Recitative (alto)

Aria (bass)

Recitative (soprano)

Chorale

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Bach's cantata, BWV 8 was first performed at the Sunday service at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig on September 24, 1724, during his second season of writing a weekly cantata. Its opening chorus and the closing chorale are based on the seventeenth-century hymn Liebster Gott, wann werd ich sterben? (Dearest God, when will I die?), for which Daniel Vetter, one of Bach's organist predecessors in Leipzig, had written the melody.

In the opening movement, the chorus sings the phrases of the chorale on the text, "When will I die? My time is constantly running out…" Against this sustained music, two oboes d'amore play a duet over pizzicato violins and viola. It is a beautiful, transparent sonority over which a flute periodically plays repeated bell-like sixteenth notes. Each group of the flute's sixteenths has twenty-four notes, suggesting the passing of time as mentioned in the words of the hymn. A colla parte horn plays the chorale tune along with the sopranos of the chorus.

In the aria that follows, a tenor is accompanied only by a solo oboe d'amore and continuo. The bass line continues the pizzicato from the opening chorus, as the beats of its four-note motive emphasize the fear in the words "wenn meine letzte Stunde schlägt" ("if my last hour strikes"). Following an accompanied recitative for alto, the bass aria banishes fears of death and turns to Jesus. It is a joyful aria in the character of a gigue, with a prominent flute solo accompanied by strings and continuo. A secco recitative for soprano then leads into the closing chorale. It is, as mentioned above, the chorale by the Leipzig organist Daniel Vetter, but here Bach, atypically for him, does not harmonize the chorale tune himself but uses Vetter's full harmonization.

Bach seems to have had a particularly fine flutist for several months around the time of this cantata, for he wrote expressive and sometimes quite difficult flute parts during that time. The flute in the opening chorus and in the bass aria of this cantata has extreme high notes for a Baroque flute, its music in the aria going up to a high "A." Whether the original flutist could play the highest notes is unknown, but Bach subsequently made some alterations, first adjusting the part for a "flauto piccolo" (perhaps a recorder), then making other alterations for a performance in the late 1730's, and finally transposing the cantata down a step in the 1740's. But since transposing this music sacrifices some of the beautiful sonority of the opening chorus, the cantata is normally played in its original form today. The high notes are easily playable on a modern flute, and there are now a number of Baroque flute players, as well, who can manage them.

Boston Baroque Performances

Liebster Gott, wann werd ich sterben?, BWV 8

April 12, 1985

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Sergio Pelacani, countertenor

Frank Kelley, tenor

James Maddalena, bass

Jesu, der du meine Seele, BWV 78

Cantata for the fourteenth Sunday after Trinity

First performance: Leipzig, September 10, 1724

Soloists: Soprano, alto, tenor, bass

Chorus (S-A-T-B)

Orchestra: Flute, 2 oboes, strings, continuo

(horn colla parte with chorus sopranos)

***

Chorus

Duet (soprano, alto)

Recitative (tenor)

Aria (tenor)

Recitative and arioso (bass)

Aria (bass)

Chorale

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

This popular cantata was first performed on September 10, 1724, the fourteenth Sunday after Trinity. The hymn used in the opening chorus and in the final chorale dates from the seventeenth century.

The enormously powerful opening movement is a huge chorale prelude in the dark key of G minor. Underpinning it is a four-bar descending chromatic passacaglia line that repeats throughout, mostly in the bass but sometimes in upper voices and sometimes in inversion. The movement is scored for a full ensemble of flute, two oboes, strings and continuo with the chorus. A horn doubles the sopranos in the chorale melody.

This pleading opening chorus is followed by a duet in a very different spirit. Over an exuberant, almost playful continuo, a soprano and an alto spin out lively, imitative lines as they sing of hurrying with eager steps to Jesus. In the agonized recitative that follows, the tenor exclaims, "Ach! ich bin ein Kind der Sünden" ("Ah! I am a child of sin"). It is full of ambiguous, practically atonal harmonies showing him astray and lost, until his music settles into a steadier tempo and the more stable though still dark key of C minor, as he turns to Jesus.

The remaining two arias feature solo instruments, the tenor aria a flute and the bass aria an oboe. The flute aria in particular reminds us that this cantata was written during a period of several months when Bach evidently had available to him a very fine flutist, for whom he wrote many expressive and virtuosic flute solos, including the extremely difficult ones in cantata BWV 8. The work ends with Bach's beautiful harmonization of the chorale tune that he used in the expansive opening chorus of this cantata.

Boston Baroque Performances

Jesu, der du meine Seele, BWV 78

March 18, 1983

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Janet Brown, soprano

Jeffrey Gall, countertenor

Frank Kelley, tenor

John Osborn, bass

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80

Cantata for the Reformation Festival

Soloists: Soprano, alto, tenor, bass

Chorus (S-A-T-B)

Orchestra: 2 oboes, 2 oboes d’amore, oboe da caccia, 3 trumpets, timpani, strings, continuo

***

Chorus

Aria with chorale (soprano, bass)

Recitative and arioso (bass)

Aria (soprano)

Chorale (chorus in unison)

Recitative (tenor)

Duet (alto, tenor)

Chorale

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Bach's great chorale cantata Ein feste Burg, BWV 80 went through a number of stages before it reached the form in which we hear it most often today. The earliest version, which he wrote in Weimar in 1715, is lost, but it is known to have been more modest than the piece that we have today. Among other things, that early version would not have had the work's two biggest choral movements, and its smaller orchestra would not have included trumpets and timpani and may even have had only one oboe.

Then in 1723, Bach, who was then a church cantor in Leipzig, reworked the cantata for use in the Reformation Festival on October 31. In doing so, he added a chorale at the beginning, though not yet the grand choral movement that we have now. He also added a major chorale movement in the middle of the cantata, based on a verse of the hymn that speaks of going bravely through a world filled with devils. The chorus in that movement sings the hymn tune in a resolute unison, while the orchestra surrounds it with music of devilish abandon. Altogether there were now four movements that incorporated Luther's chorale tune "Ein' feste Burg," giving the cantata an arc that progressed through four verses of the hymn.

Some years later (the exact date is uncertain), Bach again revised the cantata for a Reformation Festival, this time composing the work's crowning achievement, the complex and lengthy opening chorus based on the same hymn by Luther that was woven through the rest of the cantata. The orchestration was also filled out with oboes, as well as the lower instruments of that family, oboes d'amore and oboe da caccia.

But trumpets and timpani were still not part of the orchestra for this work, and they never were during Bach's lifetime. It was his son Wilhelm Friedemann who added them to the two large choruses approximately a decade after his father's death. It was a procedure that Bach himself had performed on some of his works, and it added a brilliance to the sound of the cantata as it is heard in most performances today.

Boston Baroque Performances

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80

March 25, 1995

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Dominique Labelle, soprano

Pamela Dellal, mezzo-soprano

Frank Kelley, tenor

Sanford Sylvan, baritone

Ich habe genug, BWV 82

Cantata for the Feast of the Purification

First performance: Leipzig, February 2, 1727

For bass soloist, oboe, strings and continuo

***

Aria: Ich habe genug

Recitative: Ich habe genug

Aria: Schlummert ein, ihr matten Augen

Recitative: Mein Gott! wann kommst das schöne: Nun!

Aria (Vivace): Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The solo cantata Ich habe genug (I have enough) was composed for the Feast of the Purification, February 2, 1727. It was performed on that occasion by a bass singer with a solo oboe, strings and continuo, but like many works of Bach, it went through several revisions. Bach initially wrote the opening aria for an alto, but on completing it, he appended an instruction that the voice part should be transposed down an octave for a bass. He then wrote the remainder of the cantata for bass. Several years later, he transposed the work up a third from C minor to E minor to adapt it for soprano and, in that higher version, substituted a flute for the oboe. Still later, he altered the clef on the voice staff to transpose it back to C minor for an alto. A final version copied out toward the end of his life is once again for bass. Why all these changes were made and what circumstances led him to make them are not known, but they probably reflect the availability of soloists at times that he wanted to perform the cantata. It is normally heard today in its bass version.

The text is by an anonymous librettist. Over its three arias, it rejects worldly fortunes and expresses serenity as it anticipates death. In the opening aria, "Ich habe genug," a gentle pulsing in the strings supports an elaborately ornamented oboe line as it weaves around the voice. The well known middle aria is a beautiful lullaby in rondo form for the solo singer with strings and continuo, "Schlummert ein, ihr matten Augen" ("Go to sleep, you weary eyes"). The eighth notes in the bass line give this aria as well a gentle pulse, a pulse that sometimes pauses, suspended in midair, at a fermata. This aria and the recitative that precedes it were copied by Bach's wife, Anna Magdalena, into her notebook. There follows a recitative that ends in a brief adagio arioso in C minor bidding farewell to the world: "Welt! gute Nacht" ("World! good night"). The cantata then concludes with a lively aria in C minor, "Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod" ("I rejoice at my death"), in which the soloist sings spirited sixteenth-note melismas on the word "freue" ("rejoice").

Boston Baroque Performances

Ich habe genug, BWV 82

January 1, 1992

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

William Sharp, bass

October 15, 1982

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

John Osborn, bass

April 30, 1982

Chandler Music Hall, Randolph, VT

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

John Osborn, bass

April 24, 1981

Choate Rosemary Hall, Wallingford, CT

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

John Osborn, bass

April 10, 1981

Rockport Opera House, Rockport, ME

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

John Osborn, bass

Erfreute Zeit im neuen Bunde, BWV 83

Cantata for the Feast of the Purification

First performance: Leipzig, February 2, 1724

Soloists: Alto, tenor, bass

Chorus (S-A-T-B) in final chorale only

Orchestra: 2 oboes, 2 horns in F, solo violin, strings, continuo

***

Aria (alto)

Intonazione e Recitativo (bass)

Aria (tenor)

Recitative (alto)

Chorale

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Bach's cantata Erfreute Zeit im neuen Bunde (Joyful time in the new covenant) was written for the Feast of the Purification on February 2, 1724. In addition to its three soloists (alto, tenor and bass), this cantata features virtuosic parts for a solo violin in its first and third movements. The strong, cheerful tone of the cantata is established at the outset in an alto aria with the full, bright sound of two oboes, two horns in F, solo violin, strings and continuo.

The second movement, an "Intonation and Recitative," is a unique work among the Bach cantatas. In it, the bass soloist intones the chant for the Nunc dimittis or Song of Simeon from the gospel of Luke, a text that was related to the gospel reading for that day's service. It sings of finding liberation in death. Against the chant, the violins and violas in unison play a two-voice canon with the bass instruments, the two parts imitating each other sometimes exactly, sometimes more freely. In the middle of this movement, the chant and canon are momentarily broken off, while the bass sings fragments of recitative, as if interpolating a commentary.

There follows an aria for tenor, "Eile, Herz, voll Freudigkeit" ("Hurry, my heart, full of joy"), in which there is once more a virtuosic violin solo, this time in running sixteenth-note triplets. Then a brief secco recitative for the alto soloist leads into the final chorale, which takes one verse from Martin Luther's paraphrase of the Nunc dimittis.

Boston Baroque Performances

Erfreute Zeit im neuen Bunde, BWV 83

March 18, 1983

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Jeffrey Gall, counter-tenor

Frank Kelley, tenor

John Osborn, bass

Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106 ("Actus Tragicus")

Funeral cantata

First performance: Mühlhausen, c. 1708

Soloists: Soprano, alto, tenor, bass

Chorus: S-A-T-B (could be soloists)

Orchestra: 2 recorders, 2 violas da gamba, continuo

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Bach's cantata Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit ("God's time is the best time"), is one of his earliest cantatas, written, it is thought, during the brief period when the 22-year-old composer held a post as church organist in Mühlhausen (1707-8). This beautiful, well-loved chamber cantata was written for a funeral, although whose funeral it was is a matter of some conjecture. The most likely candidate is Tobias Lämmerhirt, his mother's uncle with whom Bach was close. The original manuscript is lost, and the oldest surviving copy, which dates from after Bach's death, gives no clue as to the dedicatee. However, that copy does bear the title "Actus Tragicus," which has become attached to this cantata.

The work has an unusually transparent texture, with no orchestra but only two recorders, two gambas and continuo together with the vocal soloists and choir, which could be comprised of the four soloists. It is a simple, gentle, but intensely dramatic cantata that meditates on death, the continuity between life and death, and finding peace. The text uses Old Testament verses for the first part and New Testament verses for the second.

Boston Baroque Performances

Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106

March 8 & 9, 2013

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Teresa Wakim, soprano

Katherine Growdon, mezzo-soprano

Mark Sprinkle, tenor

Brad Gleim, baritone

Benjamin Henry-Moreland, bass

Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a

Secular cantata for New Year's Day

First performance: Cöthen, January 1, 1719

Soloists: Alto (Time) and tenor (Divine Providence)

Chorus (S-A-T-B) in last movement

Orchestra: 2 oboes, strings, continuo

***

Recitative (alto, tenor)

Aria (tenor)

Recitative (alto, tenor)

Aria (alto, tenor)

Recitative (alto, tenor)

Aria (alto)

Recitative (alto, tenor)

Chorus (alto, tenor, chorus)

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The rarely heard secular cantata, Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht (Time that makes the day and the year) is designated as a serenata in its libretto. Written to celebrate New Year's Day of 1719, it was a tribute to Bach's employer at the time, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. Two soloists, a tenor representing Time and an alto representing Divine Providence, sing Prince Leopold's praises and promise him continued good fortune in the new year and beyond. A choir joins the two soloists in the dance-like last movement.

Five years later, after Bach had taken up his position in Leipzig, he adapted this secular cantata (or serenata) for use as an Easter cantata, Ein Herz, das seinen Jesum lebend weiß (A heart that knows the living Jesus), BWV 134. In that version, the aria for alto and continuo was omitted, along with the recitative that proceeded it, but otherwise the new sacred text required only a few minor alterations to the music. For later performances of his Easter cantata, Bach made further revisions, including writing new recitatives.

Boston Baroque Performances

Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a

November 3, 1978

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Jeffrey Gall, countertenor

Karl Dan Sorensen, tenor

Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140

Cantata for the twenty-seventh Sunday after Trinity

First performance: Leipzig, November 25, 1731

Soloists: Soprano, tenor, bass

Chorus (SATB)

Orchestra: 2 oboes, taille, violino piccolo, strings, continuo.

(A horn doubles chorus sopranos on the hymn tune.)

(Continuo parts extant for bassoon and organ.)

***

Chorus (1st verse of chorale)

Recitative (tenor)

Duet-dialogue (soprano, bass)

Chorale (2nd verse)

Recitative (bass)

Duet-dialogue (soprano, bass)

Chorale (3rd verse)

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The chorale cantata Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme (Awake! the voice calls to us) is one of the most popular of all of Bach's cantatas. It was first performed on November 25, 1731. The chorale on which it is based comes from the end of the sixteenth century; it has only three verses, all of which are sung in this work.

The opening movement, which has been called a chorale fantasia, sets the first verse of the "Wachet auf" chorale. It begins with a stately dotted rhythm that is passed between a trio of upper strings (first and second violins plus viola) and a trio of oboes (two oboes and a taille). In modern-instrument performances, an English horn generally substitutes for the taille, i. e. the oboe da caccia or tenor oboe in F. With the choral entrance, the sopranos sing the hymn tune over the counterpoint of the lower voices, while the orchestra continues to play the dotted rhythms and other figuration.

Following a tenor recitative, there is the first of two duet dialogues between the soul (a soprano) and Christ (a bass). As the symbolic bride and bridegroom, each voice has its own text, so that soul's questions are answered by Jesus: "When will you come?"/"I am coming." Overlaid above their dialogue is a sensuous, highly ornamented solo line for a violino piccolo, a small violin tuned a minor third higher than the other violins.

The famous middle movement of this cantata sets the second verse of the chorale, with the tenor singing the hymn tune, as the violins and viola in unison play an independent melodic line. The rich sonority of the movement is thus in the middle alto-tenor range, accompanied by the continuo bass. Bach's later transcription of this movement for organ was published as one of his Schübler Chorales.

Following a recitative for bass, there is then the second duet dialogue for soprano and bass. Like the first one, this is also accompanied by a solo instrument with continuo, the soloist in this case being an oboe. In this second dialogue, the soul is now united with Jesus: "My friend is mine"/"And I am yours."

The cantata concludes with the third and last verse of the chorale text in a simple four-voice harmonization.

The autograph score of this cantata was lost after the composer's oldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, auctioned off many of his father's manuscripts to pay his own debts. However, the original parts have survived, as have manuscript scores by later copyists.

Boston Baroque Performances

Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140

March 25, 1995

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Dominique Labelle, soprano

Frank Kelley, tenor

Sanford Sylvan, baritone

Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170

Cantata for the sixth Sunday after Trinity

First performance: Leipzig, July 28, 1726

For alto solo, oboe d'amore, strings, and organ.

***

Aria

Recitative

Aria: Adagio

Recitative

Aria

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The cantata, Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust (Delightful repose, cherished pleasure of the soul) was first performed on July 28, 1726, the sixth Sunday after Trinity. It calls for a small ensemble: a single alto soloist with oboe d'amore, strings and organ. The oboe d'amore is here not an independent instrument; rather it simply doubles the first violin in the first and last aria, enriching the color of the middle range to complement that of the alto soloist. The organ, on the other hand has prominent obbligato parts in the second and third arias.

From the outset of the first aria, the ensemble creates a sense of peace and repose with slurred, repeated eighth notes. There are just hints of chromaticism where the text mentions sin and weakness.

The second aria is in a very different character. It is an Adagio in F# minor with a text that laments perverted hearts that are set against God. There is no continuo in this aria, but the organ plays an obbligato part with both hands up in the treble range. Its music is tortuous and chromatic, while the violins and viola play a bass line in unison. The organ music breaks momentarily into more agitated thirty-second notes at the phrases "Rach und Haß" ("vengeance and hatred") and "frech verlacht" ("insolently derides").

The final aria returns to D major with music that feels lively and cheerful, despite a text that says, "I am sick of living; therefore, Jesus, take me away." It is about death as the beginning of a better life. The one discordant hint in the music is the tritone with G# at the beginning of the main theme.

For a performance of this cantata later in his life, Bach substituted a flute for the the obbligato organ in the last movement, perhaps because he did not then have a second keyboard instrument to play continuo.

Boston Baroque Performances

Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170

November 4, 1977

Paine Hall, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Jeffrey Gall, countertenor

Stephen Hammer, oboe d'amore

Martin Pearlman, organ

Weichet nur betrübte Schatten, BWV 202

Cantata for a wedding

First performance: Probably before 1717

For soprano solo, oboe, strings, and continuo.

***

Aria: Adagio/Andante

Recitative

Aria: Allegro assai

Recitative

Aria: Allegro

Recitative

Aria

Recitative

Gavotte

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

This beautiful work, one of Bach's most popular secular cantatas, is written for a small ensemble: a soprano soloist with oboe, strings and continuo. Very little is known about the origins of Weichet nur betrübte Schatten (Depart, gloomy shadows) other than the fact that, as the text itself makes clear, it was written for a wedding. It has long been assumed on stylistic grounds to date from Bach's time in Cöthen (1717-23), but more recent scholarship tends to place it earlier, to the years before 1717, when Bach was employed at Weimar.

The cantata opens amidst "gloomy shadows, frost, and winds," as gently rising arpeggios in the strings create a misty atmosphere and the solo oboe and soprano weave a tortuous, harmonically shifting counterpoint. As the atmosphere clears and the world is reborn, the cantata turns to thoughts of spring and love, and the music becomes simpler and more dance-like. The work ends with an actual dance, a joyous gavotte, in which the soprano sings only in the middle section, where she ornaments the dance tune: "In contentment may you see a thousand bright days of happiness."

Boston Baroque Performances

Weichet nur betrübte Schatten, BWV 202

December 31, 2007 & January 1, 2008

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Amanda Forsythe, soprano

December 31, 1997 & January 1, 1998

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Dominique Labelle, soprano

January 1, 1992

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Patrice Michaels Bedi, soprano

February 3, 1985

Essex Junction Auditorium, Essex Junction, VT

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Sharon Baker, soprano

February 6, 1981

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

November 15, 1980

Harvard Unitarian Church, Harvard, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

Non sa che sia dolore, BWV 209

A farewell cantata

First performance: Unknown

For soprano, flute, strings, and continuo.

***

Sinfonia

Recitative

Aria

Recitative

Aria

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

This work is one of only two cantatas by Bach that are in Italian. The text of Non sa che sia dolore (One knows not what sorrow is) makes it clear that it was in honor of someone who was departing. Who that person was has been a matter of speculation. One candidate has been Johann Matthias Gesner, a classical scholar and friend of Bach. He was originally from Ansbach, a town that is mentioned in the cantata, and was for several years the rector at the Thomasschule in Leipzig, where Bach also was employed. He left Leipzig for Göttingen in 1734, so if this cantata was indeed written to honor him, it would likely date from that year. On the other hand, the text also mentions sailing away on the sea and serving one's country, mentions Minerva, the goddess of defensive war, and implies that the person may be young. Thus the dedicatee might well be a young man going off to serve in the military.

Why the text is in Italian no one knows, but it is clear that the anonymous author was not a native Italian. While there are a few lines that quote Italian poetry, the grammar for the rest is often poor, and the text is sometimes odd and difficult to decipher.

However, Bach's music is, as one would expect, very fine. The work is for a soprano soloist with flute, strings and continuo. It opens with a lengthy da capo instrumental sinfonia that sounds like it could have been a movement from a (lost?) flute concerto. There then follow two soprano arias, each preceded by a recitative. The flute is a prominent soloist in both arias.

Boston Baroque Performances

Non sa che sia dolore, BWV 209

January 21, 1992

St. Anselm’s College, Manchester, NH

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

July 29, 1990

Castle Hill, Ipswich, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

Wendy Rolfe, flute

January 16, 1990

Gardner Museum, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

December 31, 1988

St. Paul’s Cathedral, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

July 15, 1987

George’s Island, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

January 1, 1986

Our Savior’s Lutheran Church, East Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

December 30, 1984

Mechanics Hall, Worcester, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

July 12, 1983

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Nancy Joyce, flute

November 3, 1982

State Street Church, Portsmouth, NH

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Janet Brown, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

November 1, 1982

Bay Chamber Concerts, Rockport, ME

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Janet Brown, soprano

Christopher Krueger, flute

April 3, 1982

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Nancy Armstong, soprano

Nancy Joyce, flute

O holder Tag, erwünschte Zeit, BWV 210

Cantata for a wedding

First performance: Leipzig, 1740s

For soprano, flute, oboe d'amore, strings and continuo.

***

Recitative

Aria: Moderato (ensemble)

Recitative

Aria (oboe d'amore, violin, continuo)

Recitative

Aria (flute, continuo)

Recitative

Aria (oboe d'amore with violins and continuo)

Accompanied recitative: A tempo giusto

Aria: Vivace (ensemble)

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

The cantata O holder Tag, erwünschte Zeit (Oh blessed day, time that is longed for) was presented at a wedding during the last decade of Bach's life, but the exact date and the names of the couple are unknown. The anonymous text addresses the couple as "great patrons" (Großer Gönner) who honor us with their favor and addresses the bridegroom as a "most esteemed man" (hochtheurer Mann), which suggests that the work was commissioned by a wealthy Leipzig family. The manuscript is copied out in a beautiful hand and bound in silk, perhaps as a gift to the newly married couple.

The cantata is scored for a soprano soloist with flute, oboe d'amore, strings and continuo. The soprano part was clearly written for an accomplished singer. Not only does it require endurance and technical agility, but it goes up to a high C# in the first aria, as well as in a later recitative. The second aria, with an oboe d'amore and violin accompanying the singer, is a lullaby that asks for the languid sounds of the music to pause ("Ruhet hie, matte Töne"), because they are not what a happy marriage needs, but the following recitative responds with praises for the power of music. The aria that follows begins with the words, "Be silent, ye flutes," and the flute that has begun the aria momentarily stops before continuing with its elaborate solo. That challenge to music too is answered in a recitative, and the aria and recitative that follow that one praise the bride and bridgegroom as patrons of the art and offer music as a wedding gift. The cantata ends with a bright aria wishing happiness to the noble couple.

The music of this cantata is, for the most part, an adaptation of an earlier cantata, O angenehme Melodie, BWV 210a, which had been written in 1729 as an homage to a visiting nobleman. It was later repeated to honor other visitors, and here with minimal alterations it was adapted for a wedding. Only the vocal line has survived from the earlier versions. It is only this wedding cantata that shows us the complete piece.

Boston Baroque Performances

O holder Tag, erwünschte Zeit, BWV 210

October 9, 1992

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloist:

Nancy Armstrong, soprano

Laßt uns sorgen, laßt uns wachen, BWV 213

(Hercules auf dem Scheidewege)

Dramma per musica

Libretto by Picander

First performance: Leipzig, September 5, 1733

Soloists: Hercules (alto), Pleasure (soprano), Virtue (tenor), Mercury (bass), Echo (alto)

Chorus (S-A-T-B)

Orchestra: 2 oboes, oboe d'amore, 2 horns in F, strings, continuo

***

Chorus

Recitative (Hercules)

Aria (Pleasure)

Recitative (Pleasure, Virtue)

Aria (Hercules, Echo)

Recitative (Virtue)

Aria (Virtue)

Recitative (Virtue)

Aria (Hercules)

Recitative (Hercules, Virtue)

Duet (Hercules, Virtue)

Recitative (Mercury)

Chorus

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

This secular cantata of Bach is known by its first words Laßt uns sorgen, laßt uns wachen (Let us take care, let us keep watch) but it also is known by its title Hercules auf dem Scheidewege (Hercules at the Crossroads). It was first performed on September 5, 1733 in Zimmermann's coffee garden in Leipzig. In addition to his work as cantor of the St. Thomas Church, Bach was by that time also director of the Collegium Musicum, a local ensemble of university students and professionals that performed weekly at Zimmermann's coffeehouse during the winters and outside in his coffee garden during the summers.

The occasion for this cantata was the eleventh birthday of prince Friedrich of Saxony. Bach had a long musical relationship with the electoral court at Dresden, where the prince was heir to the throne, a relationship that eventually led to Bach's receiving a title as court composer. Over a fifteen-year period beginning in 1727, he composed a number of works for the Elector and his family. Only months before the present cantata, he dedicated the Kyrie and Gloria of his Mass in B minor to the Elector.

The problem with a very fine occasional work such as this is that once the occasion is past there may be no chance to perform the piece again. But Bach not infrequently recycled his music for use on other occasions and, in doing so, also helped to preserve it. The final chorus of this cantata, as well as a few of the solo movements, are themselves adapted from earlier religious cantatas, but Bach then adapted all the music of this cantata, aside from the dance-like final chorus, for use in his Christmas Oratorio. It is in this last incarnation that much of the music is best known today.

Hercules at the Crossroads is the kind of allegorical dramma per musica which Bach and his librettist Picander used for a number of celebratory cantatas. The story tells the legend of Hercules, who must choose between the path of Pleasure and the path of Virtue. When Pleasure attempts to seduce him with a lullaby, Hercules consults Echo for advice, who, not surprisingly, confirms Hercules' own preference for Virtue. Eventually Hercules and Virtue are united in a duet, and Mercury descends to explain that the drama has been an allegory for the eleven-year-old prince Friedrich. A "Chorus of Muses" closes the celebration with a gavotte-like song of praise in honor of the young heir to the throne.

Boston Baroque Performances

Laßt uns sorgen, laßt uns wachen, BWV 213

February 28 & March 2, 2002

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

David Walker, countertenor

William Hite, tenor

April 12, 1985

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Sharon Baker, soprano

Sergio Pelacani, countertenor

Frank Kelley, tenor

February 15, 1980

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Susan Larson, soprano

Jeffrey Gall, countertenor

Ray DeVoll, tenor

Brandenburg Concertos

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

To His Royal Highness Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg, etc., etc., etc. Sire: Since I had the happiness of playing at the command of Your Royal Highness a few years ago, and I saw that you took some pleasure in the small talents for music that Heaven has given me, and that, in taking leave of Your Royal Highness, you did me the honor of asking that I send you several of my compositions: therefore, following your gracious command, I take the liberty of offering my most humble respects to Your Royal Highness with the present concertos, which I have arranged for several instruments. . .

With these words, Bach offered to the Margrave of Brandenburg, the youngest son of the Prince-Elector, some of the most sublime music ever written. The date of the dedication was March 24, 1721, and the volume, neatly copied out in Bach's own hand, was entitled "Six concertos with several instruments. . ." (The popular title "Brandenburg Concertos" was bestowed more than a century and a half later by Bach's biographer, Philipp Spitta.)

As he says, Bach had met the Margrave and played for him only a few years earlier in Berlin, while on a visit to find a new harpsichord, and the Margrave had asked Bach to send some of his compositions. But what the Margrave thought of these concertos or whether he actually had any of them performed is unclear. There is no record that Christian Ludwig ever thanked Bach for sending his music, and the original score looks like it was never used, although, of course, copies could have been made. In fact, most of these concertos did not fit the make-up of the Margrave's personal band, whereas the ensemble that Bach was then directing at the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen would have been well suited for these concertos. Clearly, Bach did not compose the music specially for the Margrave, but gathered together in one volume six of the concertos that he had composed for his own use over a period of years.

The Brandenburgs grow out of Bach's long fascination with the latest concertos of Vivaldi and other Italian composers, and they are often cited as the culmination of that genre, but they are more than a summation. They go well beyond their models in their structure and instrumentation. Each of the six Brandenburg Concertos is scored for a different combination of instruments, and each combination is unique in the repertoire.

Of these six concerti, the second, fourth and fifth work well with either a small band of one player to a part, such as Bach seems to have had at Cöthen, or a larger ensemble with multiple strings, as would have been employed at some of the more wealthy establishments of the time.The first concerto, the early version of which precedes Bach's employment at Cöthen, has a richer orchestral texture and is better balanced with multiple strings.The third concerto, on the other hand, is likely meant for solo players on each part, for reasons discussed below.The sixth concerto too essentially a chamber piece with one player to a part, with the unusual tutti ensemble, which includes the transparent sounds of gambas, being almost the same size as the solo group.

Concerto No. 1

The first of the Brandenburg Concertos has the fullest, most complex orchestral sound of any of the six. Here, Bach calls for an orchestra divided into three choirs of instruments--strings, woodwinds and brass--and appoints solo instruments within each group. The string section of the orchestra includes a solo violino piccolo tuned a minor third higher than the normal violin. Among the woodwind group --three oboes and a bassoon -- the first oboe is often a soloist. The third group comprises two horns, which together act much like a third soloist, along with the violino piccolo and oboe.

For the first three movements, Bach creates a music of multiple layers, as the instrumental choirs imitate and answer each other with their characteristic sonorities. In the first movement, he does this for the most part without soloists. The Adagio features the solo violin and oboe, answered by the bass instruments, and, in the third movement, a solo horn joins the violin and oboe. However, in the fourth and final movement, the menuet with its trios, the choirs of instruments are treated differently. For the four repetitions of the menuet itself, all the instruments are combined into a single orchestral sonority. Each of the three middle sections, however, features a different instrumental group, the first has the woodwinds alone, the polonaise the strings alone, and the last the horns (an extraordinary accompaniment of unison oboes). The polonaise (written poloinesse in Bach's manuscript and altered to the Italian polacca in some later sources) is named for the moderately paced Polish dance.

Bach's use of horns in this concerto is remarkable. As hunting instruments, they had been employed on special occasions to depict hunting scenes, but this concerto is one of the earliest works to use horns as regular members of the orchestra. (The first version of this piece is thought to predate Handel's Water Music, another early work with orchestral horns.) Despite their newcomer status, Bach calls for a full range of virtuoso technique from the horns. Nonetheless, he reminds us of their origins at certain moments, such as at the very beginning of this concerto, where the horns play hunting calls. As if to emphasize their presence, Bach superimposes the opening horn calls onto the more traditional concerto music played by the rest of the orchestra, using a cross rhythm (triplets against the sixteenths of the orchestra); and he uses the traditional horn calls unaltered, even though some notes conflict with the harmonies of the orchestra. Bach's instruments were the natural (valveless) horns that developed directly from the hunting instrument.

There is, as mentioned, an earlier version of this first concerto, which may date from around 1713, the year of the "Hunt" Cantata (BWV 208), another work in which Bach uses horns. In 1726, five years after sending his concertos to the Margrave of Brandenburg, Bach recycled music from this concerto for use in two cantatas at Leipzig. The entire first movement forms the opening sinfonia of his cantata, BWV 52. Then, only a few weeks later, he made a more fanciful adaptation of the third movement for a celebratory secular cantata (BWV 207), using three trumpets and timpani, instead of horns, and adding a four-voice chorus.

Concerto No. 2

The unique quartet of soloists in this concerto consists of a violin, a recorder, an oboe, and a trumpet. All four are high instruments, and, together with the relatively transparent orchestral sound in much of the work, they give this concerto an unusually light texture.

The extraordinarily difficult, high trumpet part in the first and third movements is written for a rare instrument, a natural (valveless) trumpet in F. (Most Baroque trumpet music is in D or C.) The concerto is, of course, often played to excellent -- although quite different -- effect on the modern valved trumpet. While that instrument can give the part great soloistic brilliance, the lighter natural trumpet of Bach's day becomes more of an integral part of the solo quartet. (In 1950, at a time when this high trumpet part was still considered nearly unplayable, Pablo Casals made an inspired recording of it by substituting a soprano saxophone for the trumpet.)

The middle movement of this concerto is a chamber work, for only the violin, oboe and recorder with continuo. The trumpet and the orchestra are tacet. While the three soloists play thematic material, the constant eighth notes in the continuo bass gently propel the piece forward.

The third movement then offers a minimal role for the orchestra. Here, the four soloists play alone with continuo for the first third of the movement, and they continue to dominate to the end without interruption from the orchestra. The orchestra enters to accompany four passages, but only the bass instruments of the orchestra are given any thematic material. The basses in this way counter-balance the high solo quartet.

Concerto No. 3